Commentary by Climate Adaptation Center CEO, Bob Bunting

Editor’s note: This post also appears in Cumberland Advisors Market Commentary, November 18, 2020

If you live along the Eastern Seaboard of North America or the Gulf Coast, or in the Caribbean or Central America, hurricanes have been on your mind these past few years, and with good reason! The last four years have been barnburners, and this year set an all-time record for tropical storms.

The average number of storms in a normal hurricane season is just 10. Starting in 2017, we have seen the number of storms grow year by year from 12 to 15, 18, and now 30 so far in 2020. Before we discuss why this unmistakable trend has emerged, let me spend a minute on how these amazing, fascinating, and sometimes terrifying storms naturally form.

How Do Hurricanes Form?

Hurricanes start with the evaporation of warm seawater, which pumps water vapor into the lower atmosphere where the sea and the air meet. Nothing happens unless there is already a disturbance of some kind present. That could be any weather event where there is already some upward motion in the atmosphere. Typically, it’s a clump of thundershowers that provide the necessary convergence of winds to focus the rising air. As air rises to higher altitudes and cools, water vapor starts to condense into clouds and rain. That process releases heat that warms the surrounding air. As the air far above the sea rushes upward, even more warm, moist air spirals in along the sea–air interface to replace it. Sea-level air pressure at the center falls further and further, creating stronger and stronger rotating winds around the center. Here we go!

Thinking in 3 three dimensions now, as long as the bottom of this weather system remains anchored to the warm seawater and its top is not blown off center by shearing high-altitude winds, the system can strengthen and grow from a depression to a tropical storm and possibly a hurricane.

Warming Oceans Are Leading to Explosive Hurricane Development

The process from disturbance to hurricane or major hurricane usually takes days, but things are changing! As the climate has warmed, worldwide temperatures have steadily increased since 1850, and almost all the years of the 21st century so far are among the top 20 warmest, so hurricanes now have warmer seas to feed energy into them. In 2017 I coined a term to describe what I believe is a step function in rapid hurricane development. I call it Explosive Development; NOAA uses that term Rapid Intensification, which means an increase in wind speed of 35 mph in a tropical storm or hurricane within a 24 hour period. But the term doesn’t quite capture the meaning in a way the public can relate to, so at the Climate Adaptation Center we use “explosive development.”

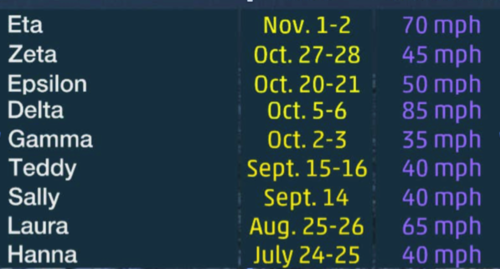

Just this year, nine storms have exhibited this explosive behavior, and some have set intensification records, including Laura, Eta, and Delta, all of which made US landfall. It’s been a record year for US direct hits by tropical storms. Twelve have struck the US, and the season is not over yet! Up until now, the highest number of storm hits in the US was nine in 1916.

The Weather Channel’s tally for rapid intensification is shown above. Image: The Weather Channel

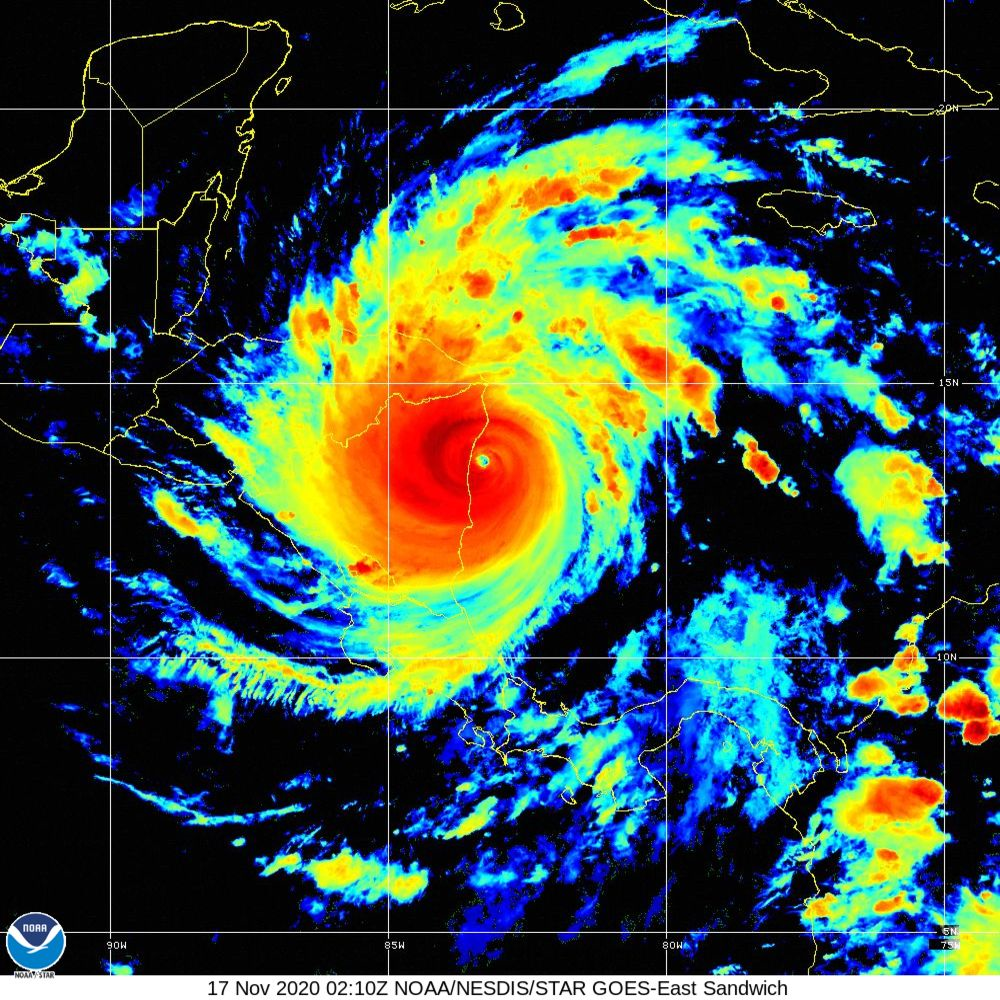

Eta intensified from a tropical depression to 155-mph sustained winds in just 36 hours! Imagine if Eta had done that just off the coast of the US and then hit a major metro area. Eta took a terrible toll in Central America, with hundreds killed, fierce floods, and widespread damage to crops that could create humanitarian crises in the months ahead. Now Iota is forming and appears likely to take a path similar to Eta’s and create a second serious hit in the same place!

The trend toward more rapidly developing storms may be far from peaking. Researchers at MIT, led by colleague Dr. Kerry Emanuel, used a computer study that compared hurricanes generated from 1979 to 2005 and then, based on expected climate warming by 2100, ran another simulation. The frequency of storms rapidly intensifying near a coastline with an increase in wind intensity of 70 mph or more in a 24-hour period increased from one such storm in a hundred years to one every 5–10 years. That’s an increase of 10 to 20 times and further confirms my own predictions on this subject. Other scientists have done similar work, and while details differ, all studies lead to the same general conclusion. The risk of catastrophe is rising along populated coastlines of North America; risk management is becoming an ever more urgent activity; and that is what we need to get about doing!

Hurricanes Are Developing Faster, But Moving Slower

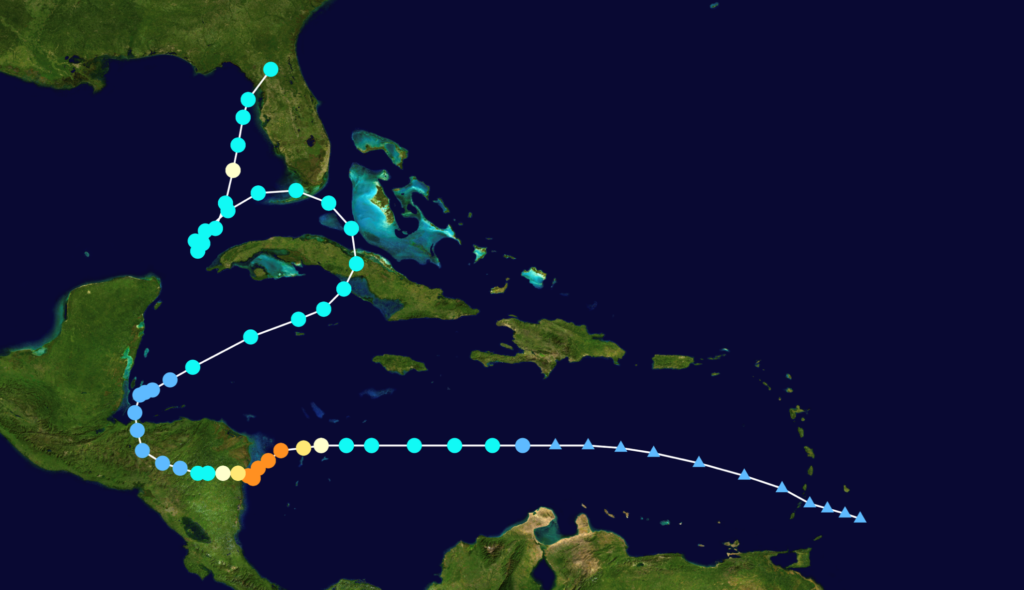

Hurricanes are also displaying two other changes in characteristics that are adding to risk. The first is that they are slowing down because the Earth is warming faster at the poles than at the equator. As that happens, the temperature difference between pole and equator decreases, slowing the steering winds that move weather systems. Hurricanes are stalling more frequently. We saw that with Harvey in Texas, Florence in the Carolinas, Dorian over the Bahamas, and Eta over Central America and the Gulf of Mexico. In each case, not only did storm winds do more damage but also rainfall caused epic flooding. Harvey set a world record of over 60 inches, and Eta probably dumped a similar amount in Central America.

The track of Eta makes the point about slower movement.

The dots in the image above indicate movement in 12-hour periods, and colors show the intensity of the storm. Orange is Cat 4. Imagine the situation if Honduras were instead Houston, Tampa, Miami, NYC, or Boston and a tropical depression rapidly increased to a Cat 4 or Cat 5 storm just before coming ashore and then stalling.

If that scenario were not enough, also consider that these storms that rapidly intensify often have “pinhole eye” structures that are just 10 to 15 miles wide. Eta’s was 10 miles wide; Laura’s was 20 miles wide. These small eyes concentrate the wind; and when they come ashore, they are like large EF3 tornadoes. Hurricane Michael was also a rapid intensifier with CAT 5 force and a 10-mile-wide eye. It wiped out Mexico Beach in Florida just two years ago, doing $8 billion in damage in a relatively unpopulated area.

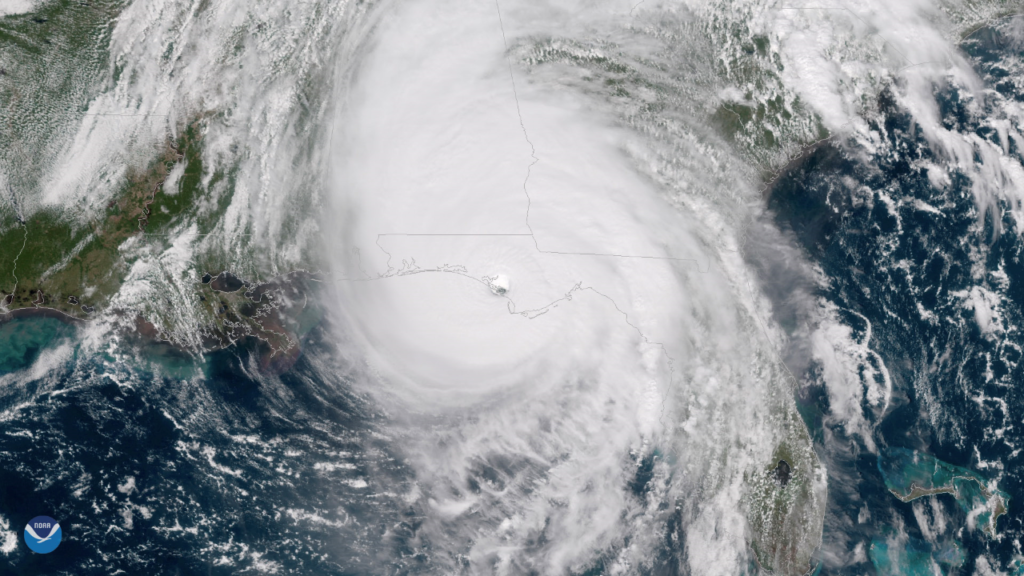

Hurricane Michael roars ashore as a Category 5, Oct 10, 2018

Damage to a major US city or cities could top $1 trillion if they were hit by a rapidly intensifying Cat 4 or Cat 5 storm. The stage could be set for a mass casualty event. Are we ready?

Still not convinced? From 1980 to 2000 there were a total of five Category 5 storms in the Atlantic basin. The basin includes the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic Ocean. Since 2000, there have been 14 Category 5 hurricanes; and should Hurricane Eta be reclassified as a Category 5, as I suspect it will when site surveys are complete, then the total will be 15.

The Role of the Climate Adaptation Center

The Climate Adaptation Center (CAC) chose Sarasota Florida for its initial location partly because of the area’s many climate-driven disruptions, from hurricanes to harmful algae blooms like toxic red tide and sea level rise. Climate warming is also having impacts on both human health and our natural environment.

Florida is growing by leaps and bounds and now has 22 million people, 7 million more than in 2000. Climate disruptions and the growing population are both happening at once, requiring world-class risk mitigation! The CAC provides science translated in a way that can lead toward much more effective risk management. Once we have established a successful model in Sarasota, we want to deliver a CAC that leverages effective climate adaptation in your area! To do that, we need to make the work in Sarasota a stunning success. That is what is about to happen!

Bringing our understanding of climate warming from the global level to the local level allows us to use great science to make probability-based climate forecasts similar to the weather forecasts you use every day.

Making those climate forecasts and backing them up with information and a curated science database will help decision makers in government, the private sector, and academia to speedily develop cost-effective and timely regional adaption and mitigation measures to blunt the worst impacts of climate disruptions. Not only can this strategic effort mitigate risk, it can simultaneously jump-start the Climate Economy. If we do this right, reacting to climate warming in a positive way will help build the economy and turn the threat into a wide range of opportunities.

Postscript:

While this article was in publication, the nonstop 2020 hurricane season delivered another all-time record event as Hurricane Iota crushed Central America with winds gusting to 200 mph.

Hurricane Iota at landfall in almost exactly the same place hit by Hurricane Eta 13 days earlier.

- Latest Category 5 recorded in the Atlantic Basin

- Second time in 13 days Central America hit, in the same location, by a Category 4 or Category 5 hurricane

- First time a hurricane reached Category 5 in a storm named in the Greek Alphabet

- No hurricane season has had more than 2 major hurricanes in October and November. This year we have Delta, Epsilon, Eta and Iota.

- The 15th Category 5 since 2000.

Given what we now know, please help us make the CAC successful.

While international solutions to the global climate problem evolve in the coming decades, we are focused first on the immediate need to address Florida’s present and future climate warming issues. Foremost among these are sea level rise, hazards to human health, red tide, changing hurricanes, and threats to the natural environment.

Once proven, this entrepreneurial business model will be used along with the CAC infrastructure to start CACs around the US and the world. Solutions happen on the local level.

Our mission is to build CAC into a focal point connecting the scientific community, the public sector and private enterprise to apply climate science to solving Florida’s unique challenges, while engaging Florida businesses in developing cost-effective adaptation strategies for Florida and jump-start the Climate Economy.

Broadly speaking, the Climate Economy refers to the relationships among actions that can strengthen economic performance and those that reduce the risks resulting from climate change. At global and national scales, considerable emphasis is placed on the concept of a low-carbon economy – shifts in energy consumption and production that limit greenhouse gas emissions, thus limiting future climate warming. Regional and local climate economies have a more immediate focus on adaptation and mitigation efforts.

By engaging the business community, together with the scientific community and the public sector, the first CAC creates a launch pad for new products and services for cost-effective solutions to Florida climate issues.

Help us make the climate threat into a climate opportunity!

With knowledge doubling at an ever faster rate, by 2100 we will know how to tune the climate. In the meantime, reducing risk and buying time for a wider solution is the only way to go. The bottom line is, climate disruptions are personal, and they are happening now.

I’ll leave you with a photo taken a few nights ago as Tropical Storm Eta hit Sarasota. Winds were only 52 mph, but over six inches of rain fell in just 24 hours, breaking a 100-year-old record for the date. People are saying they have never seen such tidal flooding on our protective barrier islands. A life was lost. Will insight be gained and opportunity seized?

Tropical Storm Eta hits Sarasota, FL, flooding parts of downtown. Image: Sarasota PD